The character of Jack Skellington made cracks in the fabric of heteronormative thinking with his performance of Santa Claus, skeletal reindeer and all, proving that these spaces are not permanent and can be changed– even if only for one sleigh ride.

As summer comes to a close, you hear whispers of desire in the air, wishes for cooler days, snuggly sweaters, and pumpkin flavored goodies. September knocks on the door and society opens it, welcoming the fall season with open arms and with this new season comes new societal expectations to abide by.

You can start decorating for Halloween in September, but don’t you dare start decorating for Christmas in November– it is just not right (at least that is what most of society says). This brings up the notion that holidays, in general, are just another method of enforcing norms upon the population that cause spacial divides; that cause power play between what is considered right and wrong; and that cause the establishment of normal and queer spaces.

To Sara Ahmed, a renowned gender theorist, queer is the refusal to sit comfortably in these pre-molded spaces. What is normal is heterosexual, thus the heterosexual is the norm. Those spaces are formed by the transcription of societal ideals onto bodies, thus making anything different from the ideal struggle with discomfort (428). Ahmed believes that to queer is to not simply reject the discomfort, but to embrace it and leave marks in spaces in order to rework society as a whole and disperse ideals. If one tries to enter spaces not designed for them, one will face further ostracization and consequentially, threaten the rigidity of those spaces themselves; for instance, if one starts decorating for Christmas in September, society might criticize it, but the fact that one was able to and did it in the first place shows that nothing is stopping others except the shared idea of discomfort– what is normal is fluid and only enforced by shared ideology. One is taking the discomfort produced by the instance and leaving a permanent mark of rebellion as Ahmed alluded to. We see this challenging of spaces in Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. Viewers see the film’s protagonist, Jack Skellington, attempt to make Christmas a holiday that citizens of The Town of Halloween can execute, but as the film nears its finale, viewers also see society’s retaliation against Jack and how he threatens the child, the mascot of society’s ideals.

He ultimately fails at queering the boundaries between societal spaces; however, Jack’s ability to almost steal Christmas exposes the fragility of societal norms–he makes the air in those spaces uncomfortable. His performance of Sandy Claws (and the rotten tomatoes thrown at him) expose the entire theatrical performance that is holidays. Holidays may seem to boost up underrepresented sects of society (I am looking at you, heritage & pride months), but in actuality, holidays don’t celebrate Otherness, but further reinforce the rigidity of the Other’s placement on the outskirts of society or in a single month of a twelve-month calendar year.

Jack’s ability to almost steal Christmas exposes the fragility of societal norms–he makes the air in those spaces uncomfortable.

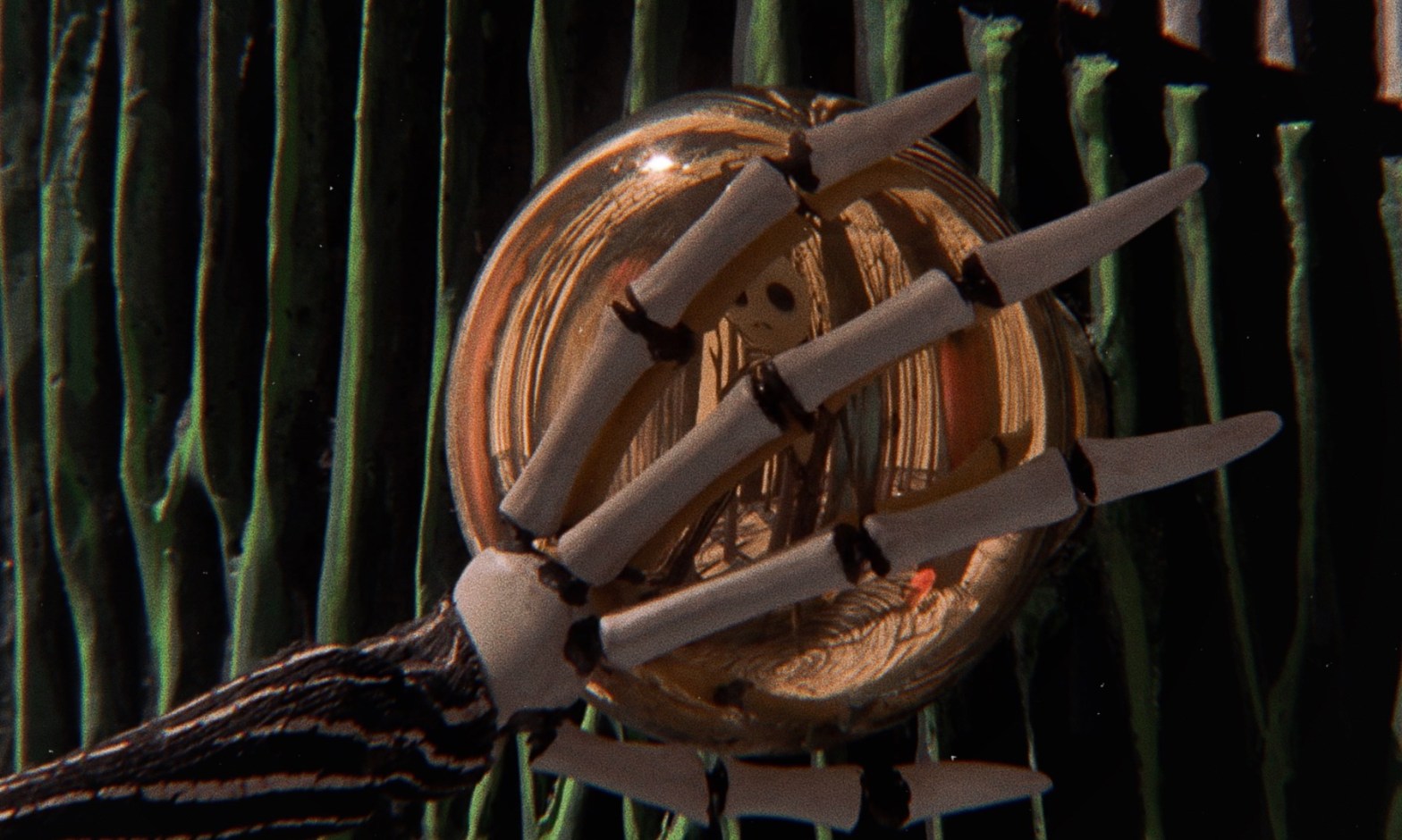

On the outskirts of Burton’s society, viewers are first introduced to a forest that holds portals to all of the Holiday Towns in this fictional world. These portals are physical manifestations of the barriers ideologically placed between normal and queer societal spaces. The portals are held in numerous trees with embellished doors on them; for instance, the Halloween portal is a tree with a jack-o-lantern shaped door.

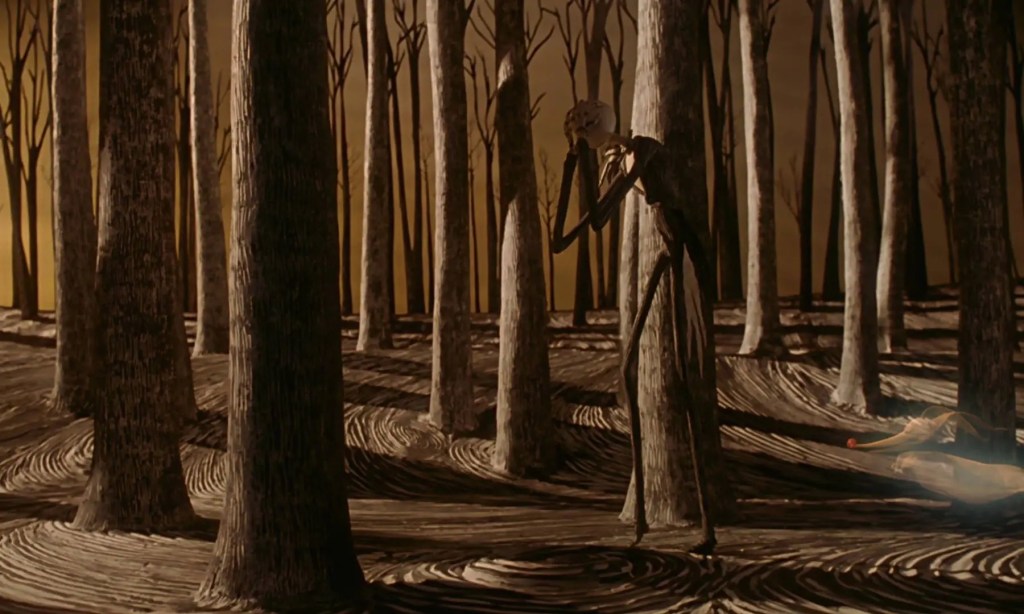

The utilization of door imagery here hints at a double meaning to viewers; while a door can be seen as a way to physically open new possibilities and horizons for people, a door can also serve as a way to lock someone in place with no flexibility or autonomy. These holiday doors are celebrated as gates to wondrous worlds of fantasy, but in reality, they are buffers between normality and queerness– they are one-way passages to designated queer spaces. At the beginning of the film, Jack is seen yearning for something new in his life– a new space. He is tired of the same Halloween routine every year. After his famous lament, he wanders through the forest, finds the portals to the other holiday towns, and enters the Christmas door. Jack physically leaves his designated space and enters another not meant for him; in his descent to Christmas Town, Jack is swirling in a spiral and disoriented.

This transition is not smooth and symbolizes how Jack is not meant to be in this space. Despite a mind-boggling fall, Jack is enamored with this town of Christmas– he is able to thrive amongst the snow and caroling. His newfound love for this foreign idea of “Christmas” is brought to viewers through a literal performance– a song allotted three minutes in the movie. This alludes to the idea that his fascination is only temporary or perhaps “just a phase,” as middle-aged parents might say. He thrives not because he fits in, but because no inhabitants of Christmas Land realize he is there. He is hidden, unknown to the people of this space–like he is not present in the space at all. Later in the film, Jack exclaims during the song “Jack’s Obsession,” that “…something [what makes Christmas special] is hidden through a door / though I do not have the key…” (Elfman). Here, door imagery returns and instead of leading Jack to a new magical world, Jack realizes the limitations of his current space.

This key to Christmas is one he will never have– it was not made for him. Burton’s use of door imagery showcases the double-edged sword that is societal spaces. One will have a space they feel comfortable in, but that space is also suffocating as it is a reminder that they are unwelcome in any other realm. It is discomfort that slams these doors off their hinges and creates fluidity in thought and mind, which is what the character of Jack Skellington creates by instead of walking away without the secret to Christmas, decides to make his own key to its specialty as he slams open his windows and shouts, “EUREKA!” to his fellow townsfolk as he willingly readies them for the incoming discomfort of difference.

Discomfort comes in many forms like a sound, a taste, a smell or a disturbing sight. There is also acceptable discomfort that society allows in small doses. For instance, Halloween is famous for its festive discomfort–goblins, ghouls, blood, witches, and anything else from nightmares. Within the month-long holiday bounds of Halloween, discomfort is allowed once a year within the realm of normality. The Town of Halloween is responsible for this holiday in The Nightmare Before Christmas. There is one town that is allowed to be uncomfortable and spooky all year round in order to fulfill the one-month requirements of the normal, mainstream spaces. The song “This Is Halloween ” is played at the beginning of the film and establishes the specific norms found in this one space. Every monster shown during this song looks different, further separating this town from the cookie cutter dreams of pedestrian life. Jack Skellington is the center of it all as he serves as the mascot of Halloween. His first introduction to the audience is a definite spectacle; a pumpkin-headed scarecrow swallows a torch and while covered in flames, jumps into a well full of mysterious green liquid only to emerge as a pin-striped suit wearing skeleton to the cheers and screams of his audience below.

Jack’s first appearance is both a performance and a transformation (Judith Butler anyone?). His theatrics are reminiscent of that of someone performing drag, further alluding to his place in this queer space. I mean, with stage names such as Bone Daddy or The Pumpkin King, who wouldn’t expect a hit loved by the audience?

Along with the introduction of The Pumpkin King, this opening sequence establishes to audiences that this is the Halloween Town inhabitants’ designated space, their only space, and it only takes up the length of a single song to explore it. Residents ask children in the audience if they want to see “something strange” because they know that people outside of their allowed sphere define them as the Other, as the strange ones (Elfman). The residents vocalize a laundry list of jobs, types of monsters, and desired characteristics possessed by the population of their town–much like any town would do– but since they differ from the defined normal, audiences feel discomfort. This is seen in the constant use of darkness and the color black; the lack of light festers feelings of discomfort and confusion in audiences. These emotions signal that this space is not safe or normal. Thus, queer lives run down the same path as heterosexual lives do–their experiences of that path are just different. One path is in the light, while the other is in darkness. Heterosexual lives are determined by their ability to continue and support dominant norms while queer lives, on the other hand, are determined by how they fail to adhere to those norms. For instance, happy colors in normal spheres are often yellow, orange, and pink whereas in Halloween Town the preferred colors are “red n’ black and slimy green” (Elfman).

To those living in normal spaces, the descriptor “slimy” might give one the heebie jeebies, but it puts a smile on the faces of those in Halloween Town. As Ahmed states, those in queer spaces are not exempt from this heteronormative narrative, but further strengthen it by displaying the effects of not following the narrative because they “remain shaped by what they fail to reproduce” (428). Both groups find pleasure in their communities, but the sources of that pleasure differ and thus, rates of acceptance vary. Chances of acceptance are severely slimmed, however, when one aspect is put into jeopardy– the child.

As aforementioned, queer is an identity that exposes that life is not a one-way, heterosexual street; this single path or dominant fantasy that the heterosexual majority devised is not the only right road. To queer something is to recognize this importance and work with it in order to remold societal spaces. However, what is deemed the ultimate getaway destination of the heterosexual road is the bearing of a child. The heterosexual road always ends in a child, and this child is the core of the dream society in all aspects–political, economic, etc. Ideal heterosexual lives are determined by their ability to continue and support dominant norms like raising a family, engaging in heterosexual sex, etc. Hence why The American Dream always includes a white picket fence. To be ideal, is to be perfect or optimal. However, fitting an ideal identity is near impossible; nobody is perfect. However, the child comes to represent perfection and pureness because of dominant images circulated throughout society. For, according to gender theorist, Lee Edelman, “the child has come to embody for us [dominant society] the telos of the social order and been enshrined as the figure for whom that order must be held in perpetual trust” (Edelman 290). A child is the ultimate goal of society because it is the dominant identity marker of heterosexuality. To identify with the child is what society aims for; a child holds much possibility and promises a stable future. A child will live on to eventually create more children, thus the child keeps current social standards alive. Edelman articulates that this fantastical child ensures the survival of the heterosexual ideal; a child will grow up, have children of its own, and the cycle repeats forever. By growing up, the former child returns to the ”imaginary past” by having a child of his or her own, and this repetition creates this fantasy of the naturalization of heterosexuality. This is where queerness enters the picture; queer sexualities disrupt this cycle of sameness and offer an alternative– an alternative of slimy greens and pumpkin kings.

The child is the ultimate reward of heterosexuality, for it ensures the continuance of the heterosexual norm and comfort of society that is threatened by queerness. Lee Edelman argues that society can queer this fantasy of the child by using the very image to expose itself and its impossibility; in short, “the efficacy of queerness, in its strategic value, resides in its capacity to expose as figural the symbolic reality that invests us as subjects insofar as it simultaneously constrains us in turn to invest ourselves in it, to cling to its fiction as reality” (292). Society is subject to this image of the child, for it runs the very core of political and social circles, but this child also makes society want to protect it; it may hold power over us, but the child needs society to save it’s innocence–heterosexual society depends upon the innocence of the child to function properly. And Otherness, which includes queerness, threatens that innocence. If children are exposed to other people, they may diverge from the prescribed narrative. Society ensures that the child “develop[s] unmarked by encounters with an ‘otherness’…unimpaired by any collision with the reality of alien desires, [and this] holds us all in check and determines that political discourse conform to the logic of a narrative in which history unfolds the future for a figural child who must never grow up” (Edelman 293). Edelman’s diction makes the child appear as a prize that must be protected and kept clean from the dangers of the Other; a child must be unmarked and unimpaired to keep its value. Unfortunately, this pristine child is not attainable, for Peter Pan is only fiction–all children grow up. Parents try to keep children innocent for as long as possible, but difference is inevitable– especially when you expect to see Santa Claus coming down the chimney and instead see a tall skeleton in a white beard that is way too big for him.

In this world of holiday lands of old, Halloweentown and, specifically, Jack Skellington represents the distinct Other ordained to one town and given one night to bring children delight and frights. This one night a year restriction is symbolic of Edelman’s thought of society wanting to protect the innocence of the child; one night of spooks and difference is fine, not much can change the course of a child’s life in one night. However, if Halloween creeps in around other times of the year, Edelman’s child is put in danger (think of marketing groups instantly de-pride monthing as soon as July 1st hits). Jack Skellington attempting to leave his defined space by taking over the space of an icon of joy, Christianity, and purity is absolutely against the predetermined norms of society– especially since he presents this persona in front of the children of the world. Jack’s queerness is seen as a threat to the child and, thus, societal normalities, which results in the police being called to shoot Jack out of the sky. To see this threat to the child in action, we must only look at the scene of the little boy receiving a shrunken head as a gift from Jack. The boy opens a seemingly normal present to which his parents seem joyous to witness until the boy turns around and shows them a shrunken head. The boy seems unfazed, showing almost no reaction at all, unlike the screaming parents.

But what are the parents screaming at? The head itself or the fact that their little boy is not screaming too. The boy does not react negatively to difference, which is the real threat to the grown-ups. Jack walks, talks, flies, and even leaves gifts like Santa Claus, but he does not look like Santa Claus and furthermore, his gifts encourage difference in thought, so his performance is a flop– it is too different. Seeing as how Santa Claus is often depicted with Christian undertones, it is no surprise that Jack, once shot from the sky, lands into the arms of an angel statue in a graveyard. Jack has been defeated by the hands of Christianity, sacrificed even given the position of Jack’s body in the scene below. Zero, the ghost dog, flies over to Jack and reattaches his jaw back to his skull. This symbolizes the idea that Jack literally lost his ability to speak up when society shot its norms back at him.

Jack represents not the lively, colorful angels in the world, but the faded stone ones that weather away in the elements. That is his spot in society. Blonde dollies and toy soldiers are sought out presents for not the children, but the parents who want to ensure their ideal child is securely in the bag.

Once the toys have been dropped in houses and the greetings have been said, Santa Claus returns society’s normalities by saving Christmas– thanks to Jack returning him his hat and starring role. Santa is the hero of the tale as his return marks a return to normalcy.

Despite society’s outlandish views of him, Jack too becomes a last-chance hero as well. Oogie Boogie, the movie’s main antagonist, represents the too scary of Halloween, the truly creepy and threatening that hides in autumnal shadows. He is even disliked by the residents of Halloweentown– he is toooooooooooo different and a true extremist. I mean, he is literally made of bugs, so he is a giant creepy crawly mask of a being.

Unfortunately, Oogie Boogie is what is commonly perceived of Halloween in this fictional land as he is “the shadow on the moon” at night, a natural element seen across the world every single night of the year regardless of the time of year. Oogie’s extremist self-portrayal reinforces the idea that the different and the Other needs to be kept under close supervision.

This is very reminiscent of the outspoken extremists that overpower queer spaces in our reality and create a bad rep for queer spaces in many modern media outlets. The fact that Jack saves Santa Claus from Oogie shows that even in this societally designated space of Otherness, however, there is difference. No one sect of society will perfectly fit everyone despite what heterosexual normies wish for; despite it being creepy, sharp, and spooky, there is still room for soft snow in Halloweentown. These boundaries ideologically created and reinforced decade after decade are as malleable as snow after a fresh snowfall.

Jack might not have been able to steal Christmas, but he made leaps and bounds in stealing space in normative social spaces. The character of Jack Skellington made cracks in the fabric of heteronormative thinking with his performance of Santa Claus– skeletal reindeer and all, proving that these spaces are not permanent and can be changed– even if only for one sleigh ride. Heterosexual society obsessively banks on the innocence of the child to the point of restricting them from exposure to all difference and intersectionality. To combat this, we all need to find our skeletal reindeer and coffin sleighs so we too can redefine what normal is, but do not do it for me– do it for the kids.

This post belongs to my category titled “Extra Crispy Hot Takes,” in which I take either a show, book, movie or song and analyze its themes and plot while looking through a selected theoretical lens.